The Under Performance of Gold Miners Proves The Case For (Some of) Them

The typical stock does not have a direct finite supply of goods or services to sell. Microsoft can create an endless amount of software and will never run out of ones and zeros to meet demand. A gold miner does not have that luxury since it is eating it’s own future with every tonne of ore recovered and gold bar shipped. A typical stock can trade at whatever PE ratio and even a stagnant non growth company can trade at a high multiple because it is assumed to still be around for decades to come. A non growth mining stock should never really trade at a PE higher than the overall mine life.

If I own a one asset gold producer with a mine that has a mine life of 10-years then it should trade at a PE of 10 today, a PE of 9 next year, and a PE of 8 a year after that etc, all else equal. If the gold producer is expected to earn $100 M per year over ten years, it should never be valued higher than $1,000 M today. Yet most investors, often including myself, tend to forget this harsh reality.

Another way to put it is that even a diversified gold major which is at least able to prove up as many ounces as it produces per year should still not trade higher PE than the average life o mine. Everything above that could be considered a speculative premium as it relates to the future price of gold. A doubling of earning due to higher gold prices does not necessarily change the average mine life but it does mean that a company could revalue 100% higher if one assumes the earnings to stay at those new levels.

In short: The value of a mine, assuming new ounces discovered does not outrun production, is at its peak just before the first ounce of gold is sold and only goes down hill from there.

Either you are growing or you are dying.

Now, what is the main fundamental case for gold miners?

That the industry is mining more gold than is being discovered. In other words, the industry is not replacing it’s reserves. Furthermore, the bigger you are, the harder and harder it becomes to even “run to stand still”.

Why do most miners, even the good miners, under perform in the long run?

Because the better mines they have today, the harder it will be to find at least an equal amount of similar mines in the future, to replace the current ones.

Take Kirkland Lake Gold for example. The Fosterville Gold Mine made Kirkland Lake into one of the most profitable mining companies in the world. The problem is that the Swan Zone will not last forever. If the company is unable to discovered an endless amount of Swan Zones there will come a day when the Fosterville Mine goes from being a stellar mine to “just” a good/decent mine. Ultimately all of the gold will have been mined and Kirkland Lake will not even be producing any gold from the Fosterville Mine. In other words Kirkland Lake must find a “new Fosterville” before the old Fosterville has run out of ore just to stand still. That is of course a tall ask.

Kirkland Lake was just an example, but it holds true for any gold miner. If a given gold miner has four mines operating and all have a 10-year mine life, the company must discover and build four similar mines within 10-years in order to just stay the same. Again, if said company is able to fully replenish it’s reserves every year and keep the average mine life at ten years, it should still never be valued higher than PE 10 at any given time. A company with an average 10 year mine life, but with little net growth prospects, which is trading at PE of 5 “only” has a 100% upside before it becomes fully priced.

The gold mining business is very different to “regular” businesses where very little is finite per definition. If a regular company has some great software product for example then there is no real limits to how much product it can produce. The ones and zeros does not run out. This also makes it obvious why the mining sector have very few companies that could to turn into “compounders”. If a junior company has one project, then that project defines the “market” for that junior. All growth will come from and be limited by the potential within that single project. If the junior is able to put that project into production then value might have already peaked and it enters a new phase of being forced to outrun the production through exploration within that project or buy another project which might have growth potential. Given that getting even one mine into production is a miracle, the idea of a junior being able to be a continual grower is rare to say the least.

The only cases that makes sense: Owning companies that will get sold at peak valuations or companies with a long run way for growth.

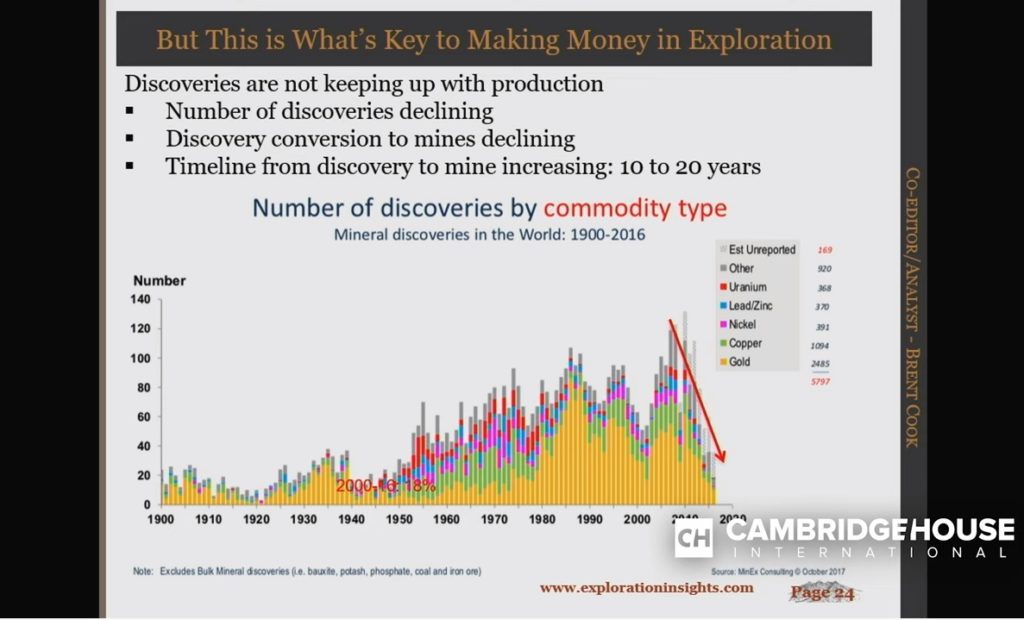

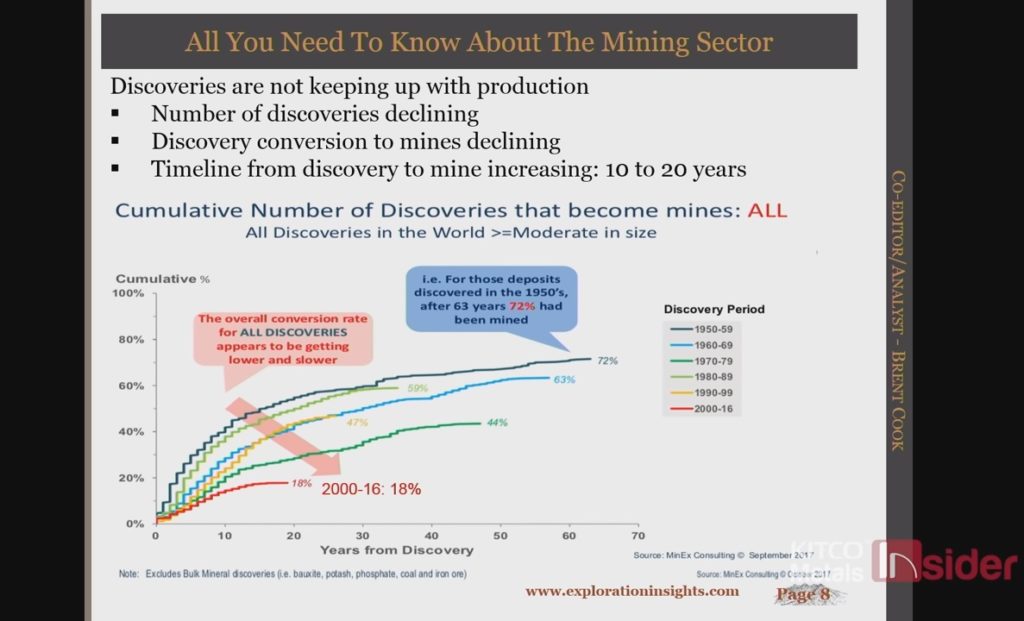

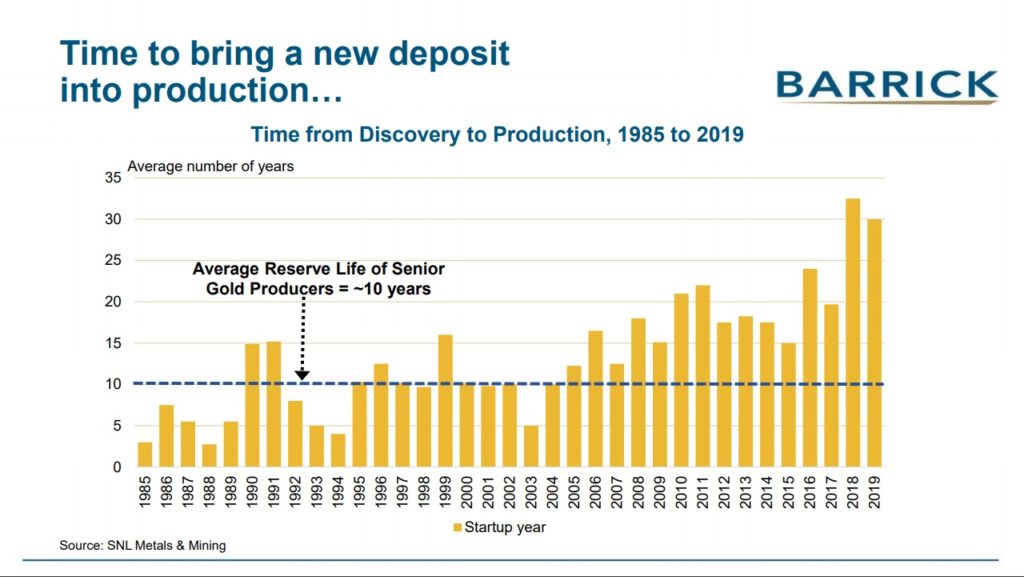

… That harsh reality coupled with the fact that the average time from discovery to production for a given prospect is over 10-20+ years today makes this extremely hard to pull off. If that wasn’t enough, the industry is simply not even finding as much gold as it did a few decades ago. Below are two slides from presentations done by Brent Cook which high lights the problems facing the gold mining industry:

To sum up:

- Time from discovery to putting a mine into production is at an all time high

- Numbers of discoveries per year is near all time lows and especially good ones

If that wasn’t enough, most miners can’t keep their cost profile in check to even take the expected advantage of a rising gold price as evidenced by the blow out in CAPEX and low margins seen during the last peak in gold.

And again, consider the fact that PE and mine life should be linked. If a gold producer made a large acquisition for an asset with a 15-year mine life that churned out $500 M in profit per year than it should theoretically be worth no more than $7.5 B (and that’s probably over priced when including time value of money, high discount rate, political risks and operational risks). If gold then went from say $1,900 down to $1,200 and the annual profit decreased to $50 M then it would be worth $750 M at a PE of 15. That’s quite a write down. This is why timing is so important. You want to own the ones that acquire assets at low prices (low PE or expected PE) that can get revalued when the price of gold is more likely to head higher than lower, which would make the acquisition more valuable even if the PE ratio didn’t expand.

This is one reason why I don’t particularly like the popular royalty and streaming companies at the moment. Franco is trading at an Expected PE ratio of 43.4 for 2020 and 41.1 for 2021. All else equal, it would take over 40 years to get your investment back. This could be explained by anticipation of growth of course (I am not up to speed with Franco Nevada so I don’t really know). With that said, you could buy Johnson & Johnson for an Expected PE of 17.2 for 2020, today. Franco Nevada’s profits would have to more than double to come down to the same PE as Johnson & Johnson. Furthermore, it would become much harder for Franco Nevada to run just in order to stand still. Then add that the increased interest in creating royalty and streaming companies means that the amount of projects that doesn’t already have a royalty/stream on them is decreasing quickly (and we know that new discoveries are already at all time lows). In contrast, if we just would assume that Franco would be stagnant, the current PE ratio would indicate an average life of mine of over 40 years for the underlying production profile. I find that highly unlikely.

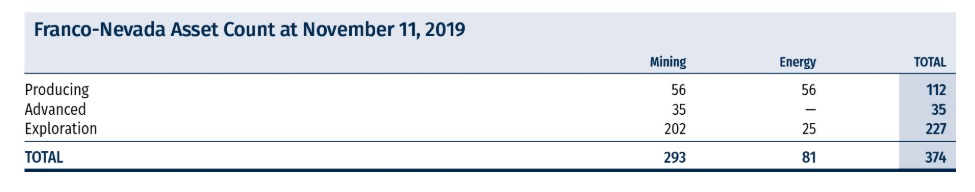

This is a summary of Franco Nevada’s assets:

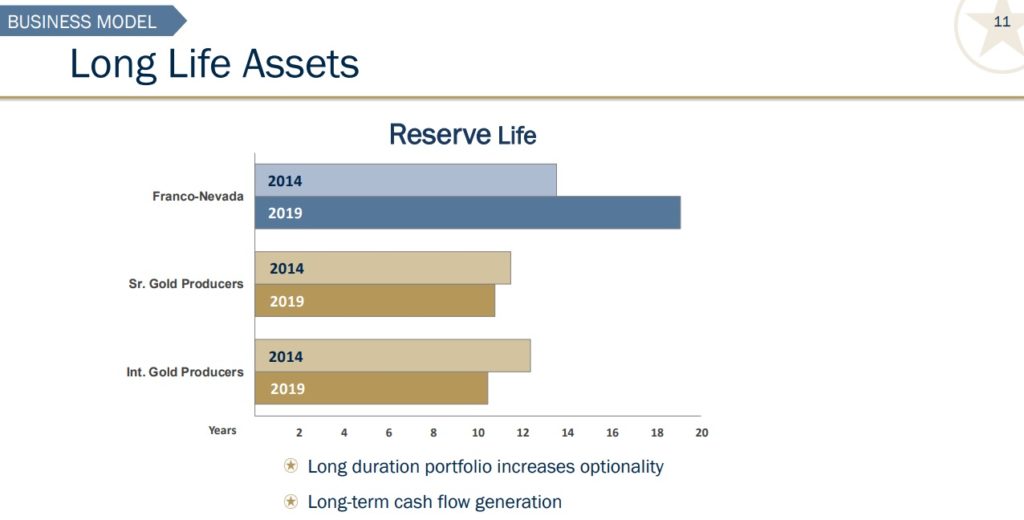

This is a summary of Franco Nevada’s mine life for underlying assets:

Obviously, Franco Nevada deserves a much higher PE ratio than most miners based on reserve life alone. It is also much more diversified and has a large exploration portfolio which should help replace or even grow the cash flow in the future. With that said, a PE of over 40 is quite high. Will Franco be able to double their earning, all else equal, in the near future and currently be trading at a forward PE of 20? Perhaps. If that’s the case it would also, all else equal, assume an average asset life of 20 years at twice the earning power compared to today. Franco will of course still revalue based on commodity prices just like every other company which derives it’s revenue from the selling of commodities.

Lets look at Sandstorm Gold instead. It is currently trading at an Expected PE ratio of 42.2 for 2020. However, in 2024 the attributed gold production is expected to increase from 65 Koz to 125 Koz and Cash Flow From Operations is expected to grow from $77 M to $135 M according to the company. If that happens then one could say that Sandstorm is pricing in a PE of around 20, in four years. It would then assume that the average mine life of the underlying production profile in the year 2024 is either 20 years or that there is more expected growth to come after that.

Keep in mind that the examples above are very simplistic and that the reality is much more complex with a lot of moving parts. Some mines will be dying when others are starting up so there will be many overlaps in terms of mine life cycles etc. Still, there are not as many gold deposits found today as it used to be and the time to build a mine has been increasing for some time. Streamers/royalty companies should saturate their market before any other type of company. With that said, they have the benefit of being able to participate in a future where deposits which make no sense today might “suddenly” start being worth putting into production. I guess I see streamers as overvalued at the moment due to a speculative premium, based on the belief of a rising gold price, but at the same time having sort of an “option” on a coming supply crunch. I mean a meaningful projects on the books might look better and better and get more money spent on them if gold goes a lot higher. However, it should take many years for said option to start paying off even if we soon find ourselves in a world where gold has permanently passed $2,000 due to the time it takes to put (currently) marginal projects into production.

Lets look at Barrick Gold. It’s trading at an Expected PE of 24.3 for 2020. Could they at least maintain the current production profile for 24.3 years? I kinda doubt that based on one of their own slides:

Again, the average senior producer shouldn’t really be valued higher than a PE of 10 today based on that graph. Then PE 9 next year and PE 8 the year after that. They should be able to maintain a PE of 10 or more only if they are successful in replacing all the reserves they mine every year and more. However, a PE ratio of 10 will result in a much higher valuation with gold at $2,000 than with gold at $1,600 of course. When we see $2,000 for gold it will also mean that more ounces will be able to converted to reserves. Anyway you slice it, senior gold producers are IMHO trading with a speculative premium based on the belief that gold will go higher and that goes for the popular royalty/streaming companies as well (again, IMHO). What is even worse is that almost no producer showed that its margins widened accordingly during the last bull market as I mentioned earlier!

High PE ratios today either assumes a rising gold price and/or future growth. The problem is that the former is a speculative premium and the latter means that it will be even harder for the company to run just in order to stand still. As soon as the new (growth) asset is operational it will start to decline in value. In other words; As soon as the growth kicks in the fuse to replace it is lit.

The only real way I can see for a producer to flourish over time is if it is founded on a world class asset and is able to use that cash flow to acquire undervalued assets… And how often does that happen?

My take:

- The large producers and streamers, who needs a lot of future supply in a world where the supply is dwindling, are trading with speculative premiums (and don’t get me started on silver producers)

- They will have it harder and harder just to keep up their current production profile

- The actual supply in the form of developers and advanced explorers are cheap

- Developers/advanced explorers should become more and more valuable as the mining companies become more desperate to stay still or even grow

- Thus, the decline in senior producers ties into the rise of the late stage explorers and developers

Additional Thoughts:

- Junior to mid tier producers that are trading at a forward PE of sub 5 are cheap because it assumes an average mine life of 5+ years even though:

- The average mine life is usually higher

- Smaller producers have an easier time to replace reserves and/or even grow

- Even though ounces that are marginal today, will be economic in the future, the high quality deposits today will be worth a lot more

- The royalty/streaming market is probably already quite saturated

- Franco Nevada would need to do deals on 374 similar projects to double it’s asset base!

- Permitted or close to permitted projects should be trading at a premium given the proximity to the supply crunch

- Long lived assets should become very valuable going forward

Closing Thoughts

Investment returns in gold miners have been poor because a) Investors have been overpaying for miners, b) gold miners are overpaying for assets, c) gold miners have not shown to be able to keep costs down when gold is rising and d) The larger they are the harder they will fall due to the difficulties of replacing/increasing reserves when discoveries are down and time to build a mine is going up.

Again: I feel like a lot of people, often including myself, subconsciously forgets about the simple fact that every mine is finite.

The very nature of the gold mining business basically forces most people to become traders simply due to the fact that there are so few cases that could be considered to be good investment cases. Just look at Barrick Gold’s long term chart:

Without having gone too indepth on Barrick it sure does look like it had an early “growth phase” and then has been in the “Mature PE phase” for many years, where the valuation is simply adjusting for the present margins and mine life, with periods of over/under valuation. This is why I dislike stagnant companies where the only change in value comes from a change in gold price.

The thoughts in this article should probably make it even more obvious why my big three are Novo Resources, Irving Resources and Lion One Metals. The simple reasons are that Novo is the only junior with such a vast pipeline of projects (and land holdings) that it could theoretically become a true long term compounding growth stock without ever needing to acquire projects in a hot (over priced) market environment in order to continue growing. Irving and Lion One on the other hand have gigantic projects with both probable upside and huge potential upside, which should allow them to grow for many years and if/when they are bought out, they should be at peak valuations. Meanwhile the average junior is sitting with one average flagship project which will probably never become a mine.

Lastly, I would say that it probably shouldn’t come as a surprise that the more “mature” and “safe” companies have a seemingly speculative premium reflected in their valuations. I mean this is the gold industry and one could assume that people investing in it are investing because they are bullish on the outlook for gold. That does not mean that I as a value investor want to pay for that premium however. I prefer to buy something cheap with good organic growth prospects instead. In essence what I am primarily looking for is growth companies that have a shot at owning a long lived asset(s) which should be very desirable when the supply crunch really hits. I also much prefer to own a company with loads of organic growth opportunities than owning a company that will need to acquire assets in the future in order to grow since most companies tend to buy high and be forced to sell low.

Always remember this: A mining company is either growing or dying.

Not: This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I own shares of Novo Resources, Irving Resources and Lion One Metals which I have all bought in the open market. Novo Resources and Lion One Metals are banner sponsors.

The PE relationships you mention don’t include the common ‘good-will’ corp’s have (don’t miners have goodwill), nor the talent of management, the learning experience gained via discovery and development, nor the use of proceeds/earnings to further development/discovery within project or beyond, the possible spinoff of assets. the possibility of buyout/takeover. Different miners support the different levels of development debt and thus deserve some credit (+/-) via PE. QH imho would be a good example of a plus PE.

It is implicitly included since earnings is a reality which is borne out of everything you mentioned. But when looking into the future it becomes exponentially harder to estimate what the future earnings might be due to things like you just mentioned. It does seem that being serially successful and/or successful in one entity over a long period of time is truly unique in this business. Ross Beatty’s business skills is a stand out for example. He even created a successful company in the crappiest commodity in modern times (PAAS in silver). That is hard to fully appreciate.

In general, when is the best time to sell gold miners? Based on the typical cyclical curve of a gold miner, this would be right after a big discovery (juniors) and right after first gold pour (developers going into production). Do you have follow some general guidelines in choosing exit points?

I really don’t know the answer to that Niels. What I can say is that in my view pretty much 98% of companies forces you to be a trader. Very few have good enough operations (high enough margins) to flourish over a full cycle (both bull and bear market) and even fewer still will be able to keep growing at the same rate after the company has become mature. If we are talking specific types of companies that can give good returns with a “hands off” investing strategy it would be juniors after a good discovery as you say. If one is certain that said company will be acquired then it’s just a waiting game until a natural exit for shareholders (easier said than done to spot what companies will most certainly be acquired though). Another strategy backed by data is to buy a developer when it is transitioning to become a producer due to the fact that many investors are too impatient to stick around for 12-24 months with little news flow leading up to production. When the first gold bar is poured, the value of the mine will then likely have peaked. This sector is beyond easy! Best regards